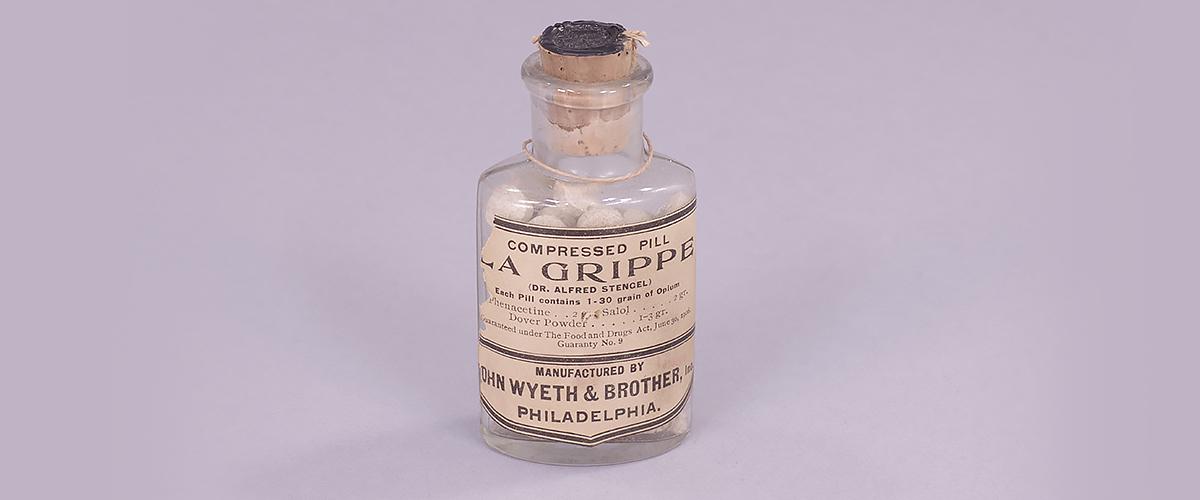

La Grippe Bottle

Dimensions:

1.75” W x 3.5” H x 1.25” DAccession Number:

2004.2.33“La grippe,” or influenza (flu), inflicted several different symptoms on those who contracted the disease. People worldwide searched for remedies to relieve fever, fatigue, and other uncomfortable—and potentially deadly—sensations. This bottle of compressed pills illuminates some key figures who developed medicines to treat those symptoms and other ailments dating back to the 18th century. Sometimes the chemicals in those drugs could be harmful or addictive if misused, like the opium contained in each of these pills.

The bottle itself is from the early 20th century, but a key ingredient—Dover Powder—was first developed in 1732 by Thomas Dover. Dover was an English physician and adventurer who, when not inventing treatments and practicing medicine, led raiding parties, plundered villages, and traded goods and enslaved people across South America, West Africa, and the Caribbean. His most famous voyage resulted in the rescue of Alexander Selkirk, whose life inspired the titular character in Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719). To relieve pain, Dover’s powder mixed opium with ipecac, a drug that causes vomiting in specific doses. It was initially designed to treat gout, but doctors and pharmacists recommended the powder for general pains, insomnia, diarrhea, and more. The powder remained a reputable treatment until the 1930s. Its inclusion in these pills likely quieted aches and pains from the flu.

The pills were manufactured by John Wyeth & Brother, Inc., a company originally owned and operated by brothers John and Frank Wyeth in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The duo started their business shortly before the Civil War and supported the invention of a significant advancement in pill manufacturing: the rotary tablet press. The press efficiently produced uniform pills that became a hallmark of the company’s brand. Indeed, Wyeth trademarked terms like “compressed tablet” in the 1870s. These pills made from compressed powder are all the same shape and size—qualities that appealed to consumers seeking trustworthy medicines with professional packaging and presentation.

Two other pieces of information printed on the bottle’s label boosted consumers’ faith in the pills. The first is Dr. Alfred Stengel’s name. Dr. Stengel was a surgeon from Pennsylvania who taught classes at several medical schools, managed a university hospital, and wrote extensively for medical journals, among many other distinguished activities. The second is a guarantee “under the Food and Drug Act.” The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 required, in part, the inclusion of ingredient labels on consumable products. Labels empowered people with more information to make informed decisions about the foods and medicines they consumed.

Informative labels did not, however, ensure a medicine was safe. Over time, medical professionals learned that certain ingredients, including opium, were highly addictive, especially in the doses they prescribed to patients. Many medicines and treatments marketed in the early 20th century were discontinued as new studies and regulations were introduced.

Click here to view this artifact’s episode of “Stories from the Collection,” a monthly video series on the DEA Museum’s most exciting objects.